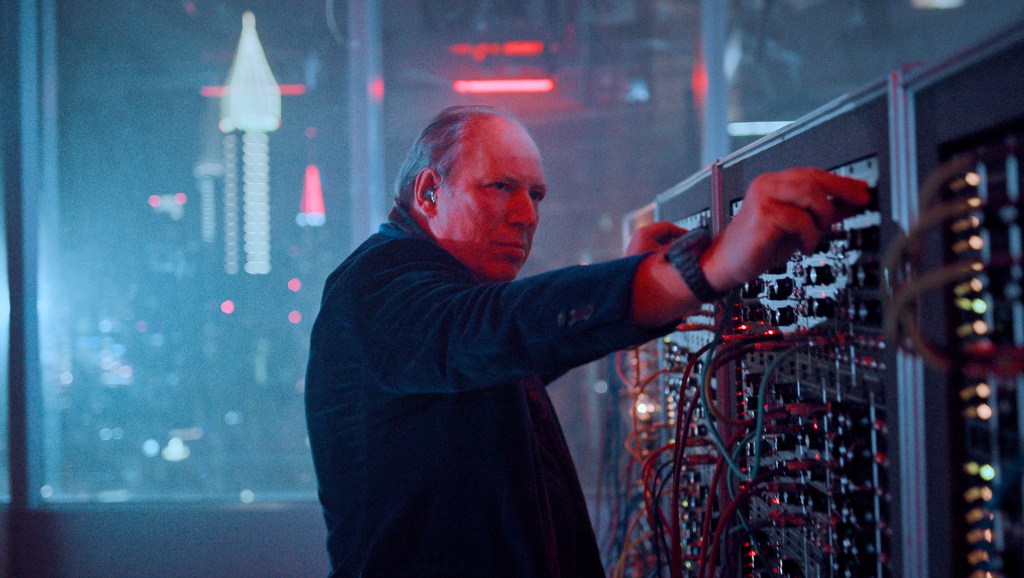

There’s a fascinating tale at play in Gbolahan Peter MacJob’s historical epic Ireke: Rise of the Maroons, a 17th-century West African story where a young prince, Atanda (Gangs of Lagos star Tobi Bakre), is betrayed by his uncle and sent into slavery after the British colonial invasion of his village as a young boy. Growing up on the Jamaican plantation, he falls in love with house servant Adunni (Atlanta Bridget Johnson) whilst enduring unspeakable hardships and brutality at the hands of his slave owners. Yet bubbling beneath the tumultuous environment is the rebel society known as the Maroons, escaped slaves on the cusp of leading a rebellion.

On the surface, you would think this is a plotline from Game of Thrones, where audiences have grown accustomed to treacherous twists and turns and acts of revenge. Heck, if you grew up like I did on Nigerian movies, such remits were a staple, to the point where you’re loading your 4th VCD disc to watch its multi-arc epic conclusion. However, MacJob’s story is inspired by true events, the first Maroon War of 1728, where Jamaicans and Africans, skilled in guerrilla warfare, worked together to fight against the white colonists for freedom. Whilst writer/director MacJob takes some creative liberties to depict this tale, there’s significant power in presenting a story that hasn’t been showcased before, especially when history has been narrated by ‘the victors’ who’ve omitted, erased and whitewashed accounts from the public consciousness. With Ireke, you’re witnessing a reclamation of history.

Yet for such a momentous story that carries a degree of bold ambition, right through its elaborate production design and prosthetics, MacJob doesn’t quite get to grips with the material. Nigerian cinema, or Nollywood as it is proudly known, has come a long way, shedding its novelty and progressing to greater heights as one of the fastest-growing movie economies in the world. In recent years, we’ve had Bolanle Austen-Peters’s powerful drama Collision Course, Daniel Emeke Oriahi’s horror thriller The Weekend and, had it not been for the biases of the Academy, Nigeria could have been celebrating its first Oscar nomination with Genevieve Nnaji’s Lionheart, disqualified over the film’s English dialogue (fact: yes, Nigerians speak English as well as several other different languages including Igbo and Yoruba). Ireke doesn’t feel like it’s cut from that same cloth, the quality feeling like a clichéd throwback of yesteryear cinema. As it grapples with complex themes of power, oppression and rebellion, it’s a storyline that goes off on multiple tangents, leaving it unable to reach its full potential.

One might expect Prince Atanda to be the leading protagonist of MacJob’s story since it begins with an injustice against him – his uncle conspiring with the British to take the throne by murdering his brother, reminiscent of a Shakespearean drama. Instead, that element is abandoned, shifting to explore the hardships and the torturous abuses of power on the plantation.

Occasionally, MacJob’s script flirts with humour, using Johnson (Wetsy Baba) as a depiction of a Black man desperate to appease his white oppressors, right down to his comical yet uncomfortable ‘Queen’s English’ impersonation. In one scene, he dines with Master Gerard (a very cockney performance by Demetri Turin), sticks out his pinky finger whilst drinking tea and comments on his disdain for his Black skin.

However, MacJob’s direction is superficial. Everything is so ‘on the nose’, heavy-handed with the dialogue and over the top in its blunt force reverie that it doesn’t allow for an emotional catharsis or engagement to seep through. Instead, audiences are entangled in the melodrama of it all. Adunni’s love for Atanda contrasts sharply with the toxic wrath felt from Lady Catherine (Alex Franklyn), who believes her house servant is having an affair with her husband, Gerard. Gerard’s actual affair with maidservant Toro (Genevieve Edwin) threatens their marriage and the plantation itself, whilst Atanda plots his escape. As for the ‘rise’ itself, the Maroon army feels all too brief.

There’s an element of MacJob biting off more than he can chew when a simpler story within its framework exists. One that is a little more patient, allowing for more character depth and focus. But there’s also a subsequent yearning to see other stories that the Black diaspora is capable of without it feeling dated. Stories about slavery and its horrors constantly force the audience to look backwards instead of forward, reinforcing stereotypes and cliches if not handled with the right integrity. Ireke may skirt between cultural importance and representation with the slave trade, but it is far too incomplete and uneven to feel satisfying.

Thankfully, when it does strive for new territory, examining African spiritualism and philosophy as a counterculture to Western lenses, that’s where the filmmaker’s efforts shine. Too often have films painted such mysticism and wisdom as “savage”, yet MacJob unpicks and finds the breathing room to expand and subsequently reward for its investment. It’s by far the most interesting element that Ireke plays with, and one wishes it spent more time in that world.

At least MacJob’s film finishes strongly, and amidst the brutality, Bakre and Bridget Johnson are the film’s heart and soul, proving the value in what Ireke poses as a story. But one wonders if such a film had had more time to gestate and refine, then maybe we would have gotten a film worthy of its subject matter.

Don’t Be Shy – Leave a Reply