WARNING: THIS POST CONTAINS SPOILERS FOR AMC’S INTERVIEW WITH THE VAMPIRE TV SERIES

I have to give Callie Petch thanks. Besides being an awesome film critic (and friend), sharing our similar tastes in film and TV culture and our occasional differences (*cough* Challengers is a great movie and I will not accept any more slander *cough*), when it comes to recommendations, Callie has been spot on.

Nothing came more highly recommended than AMC’s Interview with the Vampire, the TV adaptation of Anne Rice’s most famous and beloved vampiric novel. For context, I’ve never read the novel and it has been ages since I’ve watched the 1994 film adaptation starring Tom Cruise and Brad Pitt. To me, it feels like a forgotten memory (more on that shortly). But the repeated messaging cries of “get on this show immediately, Kel” can only mean one thing. For Callie to descend into this level of persistence, it would take something special, a show that should be on everyone’s lips in terms of discourse. I know that feeling, having done the reverse with them with Shogun, my favourite show of 2024. And as soon as the credits rolled on episode one, I was already singing its praises. Yes, I can concur, Interview with the Vampire is special.

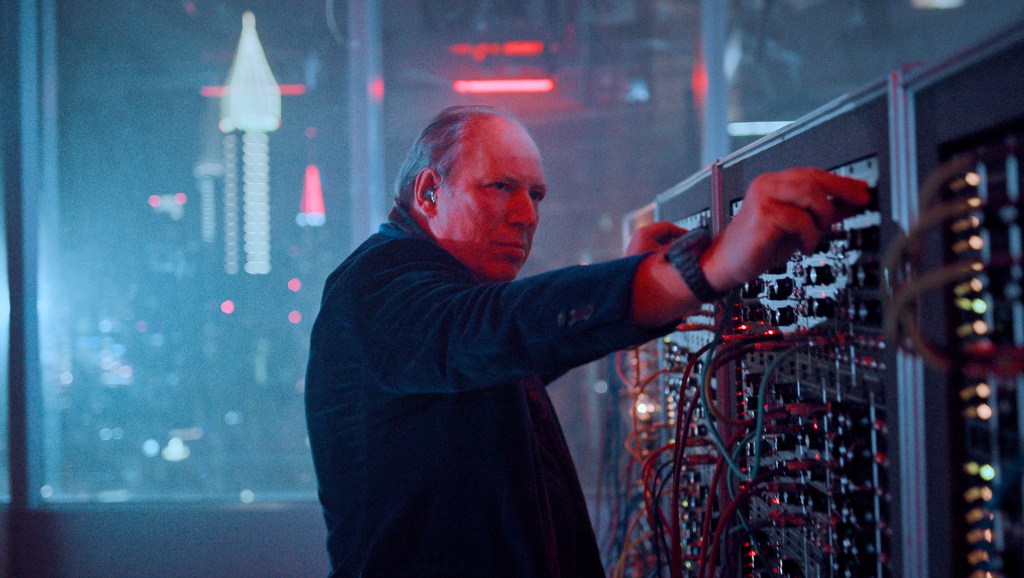

At the tail-end of 2024 and the early days of 2025, I binged watched the series and simultaneously swooned at the on-screen deliciousness of Jacob Anderson (Game of Thrones) and Sam Reid (Belle). I watched two queer lovers navigate with their immortal existence in an ever-changing landscape of world politics and social lifestyles, enthralled by their toxic, messy, unhealthy, gaslighting, abusive and complicated relationship through the decades. Between their smouldering good looks and the smoothest of accents ever committed to a TV screen, if the series was running for President, ‘Let’s Make Vampires Sexy Again’ would be its electoral-winning slogan.

Swooning aside, back to the basics shall we? For two seasons, this show ran rampage through bloodied veins and fanged veneers of Louis de Pointe du lac (Anderson). Through his viewpoint, he recalls his life amongst mortals as a vampire to journalist Daniel Malloy (a brilliantly snarky Eric Bogosian). The first season concentrated on Louis’ transformation into the undead, marked by him falling in love with the mysterious Lestat (Reid), his turbulent relationship with his family, his eventual succumbing to the dark side, and navigating the trials and tribulations as a Black man in early 20th century New Orleans. On the last point, honestly, if there’s a benefit to the race-bending characterisation, then at least it corrects the problematic storyline of Louis as a plantation slave owner!

Yet, it is the second season where the series upped its bite, fascinated by its themes of memory and recall, and Louis’ determination to get all the details right for Daniel’s book. Everyone loves to tell stories that can make us feel heroic or embellish and hide away secrets from the world. It’s why they always say, “history is written by the victors.” Yet Season 2’s examination was murky, the type where audiences embarked on a pendulum swing of emotions. It stripped their protagonists bare to the bone with every new unravelled secret and swayed back and forth on who to love, root, empathise or downright hate. Or in the case of Claudia (Bailey Bass, later replaced with Delainey Hayles for season two), who always understood the assignment when it came to her vampiric observations, those episodes will also have you screaming “f*ck these vampires!” at your screen in the same way she wrote unapologetically in her journals.

The vampires are not the “good guys”, to make things super-clear here. The show is not invested in the moral rights or wrongs of their vampiric nature, despite the constant heavy wrestling of Louis’ humanity. Behind the show’s power was the examination of characters who shaped the world into their own hubris, an image of their own wills, pleasures and dehumanising desires – and in doing so, weaves a dark and complex show.

Nothing brought that point home other than Season 2’s penultimate episode I Could Not Prevent It. Season one saw Lestat’s apparent demise, a chance for Louis and Claudia to break free from his suffocating and controlling grip. Their trip around Europe should have represented a fresh start, only to witness a world torn apart by the World War II, and having to survive on bad blood. Fast forward when Paris came calling, at the Theatre de Vampires, Louis, Claudia and her new vampire companion Madeleine (Roxane Duran) are put on trial for Lestat’s murder. Of course, Lestat was never dead, thanks to the lifeline that Louis gave to him by dumping his body in the trash. And the theatre itself was a ruse, a clever guise for the coven’s ‘out in the open’ vampiric killings (marshalled by a theatrically camp Ben Daniels as Santiago) with the audience believing it’s all part of the show. But Lestat’s presence and re-emergence at the trial exhibited all the main attributes of ‘main character syndrome’, compounding his own thirst for revenge and to inflict as much humiliation on his former companions.

The trial is an uncomfortable watch, filled with back and forth exchanges, more shocking revelations and Louis, Claudia and Madeleine powerlessly partaking in a kangaroo court. Yet, the episode’s biggest talking point was the death of Claudia that saw her, alongside her companion, burnt to ash. Her final defiant act: to stare down at every member of the audience and to remember their faces, the faces who condemned her to death with the added promise of haunting them from beyond the grave.

Claudia’s demise is heartbreaking – or as I wrote to Callie in a post-ep message, “that ep hurt like a bitch”. It was hard to shake off such a moment. It left me raging, and like any other TV character, that process of mourning felt rough. Yet, it’s no wonder she grew to become my favourite. Both Bass and Hayles were exuberant in displaying Claudia’s unapologetic nature. She was fierce, independent, curious and provided a different voice from Lestat and Louis’ turbulent love affair. She dared to be different: a vampire with dreams, longing to be free from the Lestat’s control, attributes that never waivered during her two seasons. Yet for all the promise and potential, her death reaffirms the tragedy of her life and society’s uncomfortable treatment of Black women.

To understand this level of pain, we have to chart Claudia’s inception, which also began under tragic circumstances. Based on Anne Rice’s own daughter who passed away from leukaemia at 5 years old, the 1994 film saw Claudia portrayed as a white girl, played by a young Kirsten Dunst. Claudia is used at the expense of emotional immaturity between two companions: to save her from the plague (and stop Louis from leaving), Lestat turns her into a vampire and suffers an immortal’s curse. Never being able to grow up or age only fueled her resentment towards her creators. The AMC’s version follows the same pattern: Lestat and Louis were her “angels” who saved her from a burning fire (a fallout from Louis murdering racist official Alderman Fenwick), and with a heightened metabolism, she built up a feral appetite for victims, learning the predatory instincts from Lestat and empathy from Louis. But being a Black girl is the added dimension which opens doors to new depths of her characterisation.

Claudia quickly understood she was the outsider, a third wheel that her ‘dad’ and ‘uncle’ were quick to lay down their rules to in their so-called family. After years of youthful indulgences, she played the assigned role, lavished with presents, gifts and her own naive innocence. The turning point was with Charlie (Xavier Mills), with whom she falls in love with him after several nightly courtship encounters. On one fateful evening, she accidentally takes his life after losing control and draining him of blood. In pleading with Lestat to turn him like he once did to her, he instead orders her to burn his body in the incinerator.

Lestat may have given Claudia a pivotal learning lesson: a warning that she shouldn’t get attached to mortals. Yet to inflict such trauma on a child is different altogether. It is treated as a humiliating punishment, no different from countless stories told and documented by history where Black people were forced to watch cruelty in front of their eyes (beatings and lynchings) to show what would happen if you stepped out of line. For Claudia, it was the realisation knowing she would never be treated as an equal, a context taken to another level by the growing examination of racial power dynamics in the first season. She watched Louis’ vulnerability exploited by Lestat’s extravagant dominance – and how the latter’s influence was weaving into her soul. It’s bad enough watching Louis wrestle his humanity, being repulsed by Lestat’s viewership of humanity as his playthings. Even worse when the immortal power is “gifted” by a White man.

Racism never died after President Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation and yet, Interview taps into that unnerved feeling. As we’ve seen throughout history, its practices never ended, just reshaped and retooled to serve other purposes and maintain the status quo. Here, in New Orleans, Lestat’s privilege has built an abundance of wealthy capital to live a lavish lifestyle – one that comes with its own prejudices and biases where he’s never had to confront the social construct of race. He can tempt Louis with dreams of a better (and predatory) reality, an advantage that subsequently lifts Louis’ social standings, but such gestures doesn’t change who Louis is, especially with his experiences with Tom Anderson and Alderman Fenwick on Storyville who, in their final days of business, reminded him of his place. Whilst he didn’t foresee Claudia in the picture, her existence purely threatens their vampire family and with her growing independence (as adolescent teenagers would do), he asserts his dominance by denying her access, and her happiness.

Claudia – as a Black woman – was denied a voice that would acknowledge her feelings, her perspective and her entire existence. While Louis was showered with adulation and companionship (and the simmering hatred and toxicity in the process), there was no love to begin with in Claudia. She was labeled ‘a mistake’ by Lestat when she asked him to make her a companion. In a moment of rage before Louis intervened, her life was threatened by Lestat, reiterating her as an easy target for violence. That type of microaggression channels a long history about the value of Black women, to be seen and not heard and just seemingly know our place in the system. In return, this raises the common doubts and fears about our wellbeing: we’re never good enough, we’re never pretty enough, we work too hard, we don’t work hard enough, we’re too loud, too quiet, too ambitious, too sassy, and whatever else society wants to throw as shade.

As often, Black women are seen as matriarchs of a family, and one thing that Black women are good at is recognising the red flags! She instantly recognised the control Lestat has over Louis and how Louis could not escape his maker’s control – even at the detriment of his own sanity. Yet when the inevitable ‘shit hits the fan’, it’s Black women who take care of the aftermath, sacrificing their own wellbeing for others. A case in point in Season One’s A Vile Hunger for Your Hammering Heart when Claudia nurses Louis back to health after he was dropped from the sky like a stone by Lestat.

This coincides with the adultification of Claudia. While mentally, she evolved, being forever trapped as a 14-year-old little girl was something the world kept on reminding her of. Season Two saw Claudia enamoured by the Theatre de Vampires. She’s invited to join Armand’s coven, told about the ancient vampire laws, and eventually rewarded with a starring role in their new play, My Baby Loves Window. It should have been “everything’s coming up Millhouse” moment knowing Claudia found her tribe. Instead, it became my favourite quote from the Call of Duty games: “same shit, different day”.

As Baby Lulu, Claudia plays a little child longing to be free. The two adults in her life – a maid and a rich woman – keep her locked up in her room. After the physical violence in which the audience is sprayed with fake blood, she escapes through the window and leaps to her death. They say art imitates life and vice versa, but the play is little too close to home. The play – written by the female members of the coven – can’t escape from being a tool to mock Claudia’s age, nor its minstrel-esque quality behind the performance with Claudia performing for someone’s entertainment again and again. She’s dressed like a child-like mammy figure, suffers from simulated violence every single night after being hit by a hammer, and even when she complains, having performed the play for the 500th time, Armand’s tight grip ensured Claudia obeyed. He demeans her, forcing her to live as the character off-stage by wearing the Lulu costume every night. The belittling and control is reminiscent of Child Q who, like Claudia, wasn’t protected but thrown to the wolves where she was racially discriminated against. Such measures are entrenched by positions of authority and control. In the case of Claudia, Armand deemed a threat that threatened his relationship with Louis. Knowing that she was the mastermind behind Lestat’s murder, he plotted to get rid of her in the most theatrical way possible while positioning himself as the sensitive, misunderstood outcast of the coven towards Louis.

Once again, Claudia is viewed as someone undeserving, a stereotype that Interview with the Vampire acknowledges until the bitter end. This same stereotype has been in force in Hollywood for years where Black female portrayal was regulated in the shadows, characters without agency, resilience or empowerment, forced to live in subservience of others. Even in death she’s denied respect as Santiago parades himself towards a vengeful Louis in episode eight’s And That’s the End of It. There’s Nothing Else, boasting he used her ashes as eyeshadow – words that no doubt turned another screw in the stomach lining.

The fact that I forgot about Claudia’s original fate plays into the show’s success. With memory and recall being so fallible and open to mistrust, it simply faded from my own consciousness, allowing Bass and Hayles to craft something new in its place. With the seed firmly planted in the memory banks, it seems impossible to imagine anyone else for the part should God forbid tries to do another adaptation of Anne Rice’s work. This feels definitive as Heath Ledger was as The Joker in Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight.

Despite the on-screen changes (made due to Bass signing on for the Avatar sequels films with Hayles cast the day before S2 was due to shoot), Claudia benefits from a slow-burn TV show format. Irony aside, Claudia’s growth is greatly appreciated here, getting to spend time with her wants and needs whilst trying to escape from their make-shift family. It works better than the whiplash depiction with Neil Jordan’s ‘not gay enough’ film, which feels outdated and weightless in comparison. But the casting change also works in the show’s favour, marking Louis as the unreliable narrator. His recollection of Claudia are from his memories while her fragmented diary entries (that Armand censored and ripped out) and memories were simply taken from him and forced to forget. It comes as no surprise Louis continues to remember Claudia differently, and thinking more harshly, never really knew her at all despite being her guardian. Therefore, Louis was a walking-talking embodiment of self-consumed guilt, shame and regret.

That’s a testament to Bass and Hayles, being on the same page with their character but charting different points of observation. Bass showcased Claudia’s vulnerability and innocence despite her growing vampiric appetite. Hayles showed Claudia’s maturity in a world intent on rewriting the rules, but most importantly, outgrowing her dependency Louis and Lestat brought.

Even when Lestat and Louis reconcile their differences in the season two finale, having come to terms with their guilt and sorrow for what was lost, am I supposed to feel sorry for them? Such emotions can only go so far for these ill-equipped father figures. Interview uncomfortably reminds audiences that Lestat travelled across the oceans to rehearse and perform in a play that murdered his daughter. Between Armand’s deception and Lestat’s psychic party trick, Louis was deemed more worthy to be saved. Even with one desperate look towards her “father” as she was burning alive, not even Lestat could be moved, considering the numerous times he interjected on Louis’ behalf, going as far as berating a WW2 soldier for his prejudice against gay men. It took her death for Lestat and Louis to come to terms with their impulsive actions, as well as acknowledge her value and innocence – and that within itself felt like a kick in the teeth.

Claudia’s death is entombed by how much she was failed by others – men, women and vampires alike, failed by others who took advantage, demeaned, devalued and abused her, and eventually killed her. She was a victim of a life she did not choose or consent to, a girl who was forced to grow up far too quickly – and yet was punished for it.

However, the arguments of Black female trauma won’t go away. Did Claudia need to be (trigger warning) raped to show the world’s cruelty in season one? Did her calling her execution at the Theatre de Vampires “a stoning” water down what that trial really was, a public lynching? In ‘finding her tribe’ with Madeleine, did she have to be someone who was ostracised from her own community because she had sexual intercourse with Nazi soldiers during the war? As I said before, this is a dark and complex show. The handling was far from perfect in that respect, yet you have to still give credit to showrunner Rollin Jones and the writing team.

When making these changes, Blackness wasn’t treated as an afterthought. It stood by those changes and committed to it wholeheartedly with a sensitivity and assured integration that fostered these conversations organically. It’s better than how other shows have treated Black characters within the sci-fi, horror and supernatural mediums. The Vampire Diaries notoriously had witch Bonnie (Kat Graham) as the ‘token magical negro type’, only there to serve the bewitching whims of Elena (Nina Dobrev) and her vampire love interests Stefan (Paul Wesley) and Damon (Ian Somerhalder). Star Wars has a long-standing history with its lack of care and protection towards its stars, with Moses Ingram (Obi-Wan Kenobi) and Amandla Stenberg (The Acolyte) being the recent editions where they’ve experienced rampant racist abuse and toxic backlash via social media. The studio’s silence speaks volumes when they’re very quick to hire said talent, only to leave them publicly abandoned at the first sign of trouble. The sting continued to hurt when The Acolyte was later cancelled. Even outside these genre spaces, the signs are no better with Apple TV’s Masters of the Air, where the involvement of the Tuskegee airmen were regulated to rushed background footnotes of the war. One of its advertised leading stars – Ncuti Gatwa – was barely on-screen and barely ten sentences strung together. It’s no surprise the series left a sour taste in my mouth towards its end, wishing the Tuskegee storyline had its own Band of Brothers-style series to celebrate and memorialise their involvement. It’s the least they deserve.

Where those shows failed and Interview succeeds comes down to its care and attention. Claudia had the benefit to explore the facets of her personality and agency and within that, we still felt her joy in the moments when her life wasn’t steeped in tragedy. She got to experience her first love with Charlie. She was an avid reader and explorer, keen to know about the vampire origins (more than Lestat or Louis could ever muster). Before it turned sour, we saw her fall in love with the theatre, enamoured by the on-stage trickery before landing a job with the coven. When the world repeatedly failed her, we saw Madeline choosing her when faced with death, rather than save herself. That love was later reciprocated in how Claudia held her in their last few moments. Lastly, it’s not every day someone could outsmart Lestat, be it at a game of chess or in a plot to kill him!

Claudia was unique and Bass and Hayles gave her a soul. Even in the show’s slight shortcomings, it doesn’t give off the impression of malice or ill-intention. It plays into the show’s larger themes of people living ugly, complicated lives where there are no easy, cookie-cutter answers. It resides in an uncomfortable space where the viewer has to decide what truth matters to them, and examine our own moral faith of humanity in the process. And in a medium where Black people are still fighting for accurate representation that accounts for the full spectrum of their emotional being, this is a small victory for an industry with more work to be done.

One has to hope that Rice would have loved those changes (Rice passed away in 2021) and how Interview’s lasting legacy has found new audiences (such as myself) to look at her work in a new light. Despite Claudia’s tragic end, in this iteration, she had the last laugh, exposing the vampire hierarchy for all of its nonsense – and ultimately kept it real. Now, who can forget about a character like that?

Don’t Be Shy – Leave a Reply