“Can you find the wolves in this picture?”

There’s an important revelation at the heart of Martin Scorsese’s new film Killers of the Flower Moon. It was revealed during this year’s Cannes Film Festival. His longtime passion project had undergone a script change. Killers’s original concept was a procedural drama with the FBI at its centre, investigating ‘The Reign of Terror’ murders that saw a number of prominently wealthy Osage Native Americans murdered in the 1920s. In an interview as reported by IndieWire, Scorsese said:

“At one point, after two years of working on the script, Leo came to me. And he was going to play Tom White, that Jesse plays, and said to me ‘where’s the heart of this story?’ And I had had some meetings with the Osage,” he said. “And I learned a lot about them in those three hours. I learned about the people that settled, and the stories. They’re all related to each other, and there’s still relations and there’s still issues and so-and-so is in love… and it goes on like that. And I said ‘there’s the story.’

You have to admire Scorsese for this significant change as it makes all the credible difference in Killers of the Flower Moon. There’s a powerful recontextualisation at the screenplay (which Scorsese co-writes alongside Eric Roth, which comments on history and storytelling. As two studios in Disney and Warner Bros. celebrate their centenary year, how stories are told (as mirrored by the history we’ve consumed) has looked at the past with a one-sided vision. For every story of heroic valour that is celebrated, hero-worshipped, glorified, recognised and romanticised, is also a story that has been hidden and omitted from existence.

It says a lot about history and subsequently how Hollywood has built its identity and reputation on this framework. For example, how narratives are picked and chosen? What stories are deemed important enough to live on? And what viewpoints are these stories shaped on? In a deeper context, that model of thinking has influenced how people of colour have been represented. In Gina Prince-Bythewood’s The Woman King, it was the story about the Agojie, the fearless female warriors who later inspired the creation of the Dora Milaje, who made their live action debut in Ryan Coogler’s Black Panther. Hidden Figures – the three Black female scientists, namely Katherine Johnson (Taraji P. Henson), Mary Jackson (Janelle Monáe) and Dorothy Vaughan (Octavia Spencer), who played an instrumental role in charting the next evolution of NASA space missions. HBO’s Watchmen shed light on the Tulsa 1921 Race Massacre – the Black Wall Street saw the entire neighbourhood burned and destroyed in a white supremacist terrorist attack that saw the complete destruction of Black businesses (and this disaster features in Scorsese’s film). Killers of the Flower Moon is no different, rightly putting the power of storytelling into the hands of the Osage Nation, who’ve seen Hollywood depict Native American culture in countless westerns as savages and uncultured. Admittedly, the script change and its depiction of Native American life and community could have gone further, but without this principled line of thinking – as Scorsese would describe it – he would have been ‘making a movie about all the white guys’.

At 80 years old, Scorsese’s ability to reinvent himself with every film is a reward and continued fascination. It is a longstanding knowledge that faith has always been a running theme to his films. His central protagonists, be it Henry Hill from Goodfellas, Jordan Belfort in The Wolf of Wall Street or Jake LaMotta in Raging Bull are deeply unremorseful characters. Virtue and morality always act in contradiction to the unspeakable violence and indulgence their lifestyle presents them – a world they choose freely to enter. His films are merely observers, free from judgement and allowing the audience to form their own opinions. And in the end, when these films reach their climax, accountability is paid in bloodshed (or in a moment that still haunts me to this day, Nicky Santoro’s death scene in Casino). After a fond farewell to the genre he helped redefine in The Irishman, Killers of the Flower Moon shares his familiar trademarks and motifs whilst exploring the nature of capitalist greed and its lust for power.

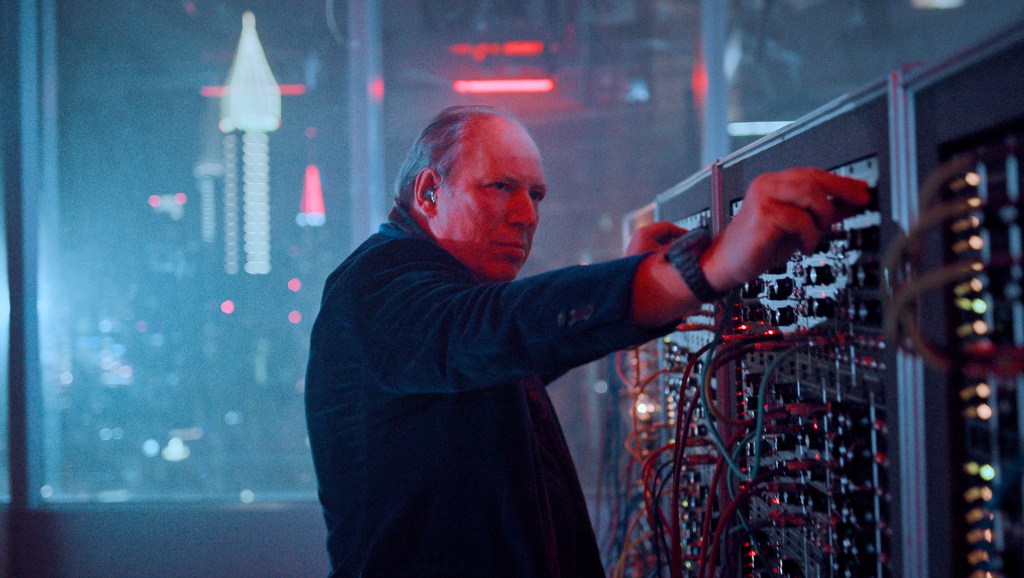

It shares a common semblance with Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer. At its core, they underpin their story with how evil works in the shadows, and like a moth to a flame, they manoeuvre through the world with ego and self-importance in order to shift up the paradigm. Nolan frames this masterfully through Robert Downey Jr.’s Lewis Strauss, who uses his bitterness and personal vendetta towards J. Robert Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) as a will to destroy his scientific reputation amongst the government. In a film that neither celebrates nor glorifies Oppenheimer’s creation of the atomic bomb, it’s the timely acknowledgement at the lack of apathy. Scorsese goes a step further in the analogy. When evil works in the shadows, this is not an individualist trait. Humanity’s worst impulse is a virus, a cancer, a disease of epidemic proportions and it has the ability to poison everything in its wake and destroy.

We see this in action from its opening frame; an intimate Native American ceremony with the mourning and remembrance of the Pipe Person. As one life ends, another begins with the discovery of oil aka ‘Black Gold’. Soon enough, the Osage Nation becomes wealthy and rich, turning their community into a profitable empire and community, thus beginning the slow decimation (and manipulation) of their culture led by William ‘King’ Hale (Robert De Niro).

De Niro (in arguably his best role in years) does a phenomenal job in playing an absolutely despicable character. He is no stranger to these roles: Travis Bickle (Taxi Driver) and James Conway (Goodfellas) are prominent examples, but in Hale, he gets under your skin, purely because of how he positions himself as a white saviour. He can integrate into the Osage community like a hero, speaking their language and providing the innocent community with amenities and access, but like a snake, is willing to destroy them from the inside. The long con comes in the form of his nephew, Ernest Burkhart (Leonardo DiCaprio) who is encouraged to integrate into the Osage community through marriage to Mollie (Lily Gladstone) and eventually inherit her ‘Black Gold’ wealth.

Scorsese explores these dynamics under a thematic microcosm where masculinity, abuse and control rage into terrorist acts for fear and escalation – and there’s no sugar-coating how brutal they are, enough to draw attention from the FBI (led by Jesse Plemons’ Tom White). Murders are showcased without remorse. Where marriage intersectionality becomes the ‘norm’, racism goes unchecked, becoming tools for white supremacy belief structures and systems. It also extends to how Hale controls his minions – in one scene, he beats Ernest with a paddle bat, punishment for his misdemeanours like a schoolboy in trouble with his headmaster.

DiCaprio’s character (doing the ‘sad, grumpy cat’ meme in every shot) is equally fascinating, playing a character caught between two worlds but where every ounce of sympathy is removed. Actions speak louder than words, and for every grave-robbing, gambling and corrupting force of nature he brings, you’re watching a stained soul growing darker with every frame.

When Scorsese is not focused on the cruelty of man and the complicit web of lies, the generous runtime offers moments with the Osage community as the audience feels the weight of their culture (including symbolism with owls) and subsequent outrage when their concerns go unanswered. Nothing sends a chill down your spine when another countless murder occurs and the tribe pledge to “act like a fire on this Earth.”

Whilst steeped in the culture, there’s a poignant scene reminiscent of Silence. Rain falls, and Ernest motions to close the window of Mollie’s home. She prevents him from happening, asking him to sit in silence with her. He’s eager to speak, but Mollie showcases the required patience. It’s a scene so delightfully simple, beautifully meditative in nature, but illustrates who has the power – and it wasn’t with Ernest.

Scorsese has been long criticised about how his films have lacked a distinct and strong female character, a notion brought up after Anna Paquin’s role in The Irishman. This is not true alongside the misguided assumption that he only makes “gangster movies” or has a hatred for the MCU. When I think about female characters, my mindset is drawn to Lorraine Bracco’s Karen from Goodfellas or my personal favourite, Sharon Stone’s Ginger McKenna in Casino, characters who’ve set the bar. However, nothing prepares you for how stunning Lily Gladstone’s performance is. She is deservedly the heartbeat and soul of the movie.

Her multilayered performance always reinforces the plight of her people. It’s her chilling introduction that gets you; unsolved murders where the deaths are swept under the carpet as she narrates. No-one cares, no one answers the call and yet her words cut like a knife. There’s power and powerlessness with Gladstone, caught in a web of injustice and people who are complicit in the corruption that has caused so much death and destruction within her family and her community.

But she also dials into a classic Scorsese archetype, a character who judges the immoral. She sees their truth – her eyes give it away as she coldly stares at Ernest and his wickedness, knowing his crimes are beyond saving. Don’t be surprised when she’s nominated for an Oscar.

Women continue to steal the show with editor Thelma Schoonmaker. As a longtime collaborator with Scorsese, Scorsese may be the visionary, but Thelma’s brings that vision to life – and she edits the hell out of Killers of the Flower Moon. At 3 hours and 26 minutes, the runtime flies by, knowing the importance of every scene to culminate to a devastating impact. But importantly, her editing reinforces a simple fact: the length of the movie is not the problem. It’s what you do with the time itself that makes or breaks it.

Scorsese seems to get better and more refined with age. I don’t know how many more films Scorsese has left within his arsenal. I hate to think of a world without him. He’s a unique director whose passion for cinema is fierce, but most importantly, he still has stories to tell that speak to the truth and heart of America. Killers of the Flower Moon is a story about injustice, and instead of shying away – just like its final frame – he leaves us with the haunting responsibility of not allowing history to repeat itself.

It is without doubt one of the best films of the year. It’s Scorsese at his masterful best, operating at the peak of his powers. To expect anything less from him would be to undervalue what he has contributed to cinema. Voices like him come once in a lifetime and Killers of the Flower Moon serves as an important cornerstone in Scorsese’s filmography.

KILLERS OF THE FLOWER MOON screened as part of the BFI’s London Film Festival 2023. Out in cinemas 20th October 2023

Don’t Be Shy – Leave a Reply